Command Division: Difference between revisions

From Star Trek: Theurgy Wiki

Auctor Lucan (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Auctor Lucan (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 57: | Line 57: | ||

The physical layout of the Tactical station console often described a sweeping curve affording an unobstructed view of the main viewer, and an equally clear view of the command stations on the bridge. This allowed for an uninterrupted exchange between the Tactical Officer and other bridge officers during critical [[operations]], as well as exchanges with crew members occupying the aft stations. The duty station console lacked a seat and was therefore a standup position, deemed ergonomically necessary for efficient tactical functions. | The physical layout of the Tactical station console often described a sweeping curve affording an unobstructed view of the main viewer, and an equally clear view of the command stations on the bridge. This allowed for an uninterrupted exchange between the Tactical Officer and other bridge officers during critical [[operations]], as well as exchanges with crew members occupying the aft stations. The duty station console lacked a seat and was therefore a standup position, deemed ergonomically necessary for efficient tactical functions. | ||

====Threat Assessment | ====Threat Assessment & Targeting System (TA & TS)==== | ||

Known colloquially as the “targeting scanners,” the Threat Assessment/Tracking/Targeting System (TA/T/TS) was a ship’s tactical sensors and computer package. The Tactical Officer relied on the TA/T/TS in combat in much the same way as the Flight Control officer uses the navigational computer — it helps him do his job better. Different classes of TA/T/TS were available; the better ones make the Tactical Officer’s job easier, but took up more space and require more power to operate. Ships may have a backup TA/T/TS system to take over for the main system if it was damaged or malfunctioned. | Known colloquially as the “targeting scanners,” the Threat Assessment/Tracking/Targeting System (TA/T/TS) was a ship’s tactical sensors and computer package. The Tactical Officer relied on the TA/T/TS in combat in much the same way as the Flight Control officer uses the navigational computer — it helps him do his job better. Different classes of TA/T/TS were available; the better ones make the Tactical Officer’s job easier, but took up more space and require more power to operate. Ships may have a backup TA/T/TS system to take over for the main system if it was damaged or malfunctioned. | ||

Revision as of 23:41, 1 October 2019

The Command Division was the corps of officers and crewmen within Starfleet who specialized in command and control functions on starbases, aboard starships, and at Starfleet Command. Members of the command division were trained in leadership and had tactical training allowing them to decisively take action in organizing and mobilizing Starfleet crews to perform missions.

Command officers included most all of the admiralty, captains, executive officers, adjutants, pilots, and CONN officers (flight controllers/helmsmen). Command division personnel also filled posts as tactical officers and sometimes in ordnance departments. [Source: Memory Alpha]

Command

This department was reserved for the ship's Commanding Officer, Executive Officer, Second Officer, and Third Officer. These three were responsible for handing out orders to the rest of the departments in order to keep the ship running. Command covered a wide range of interpersonal interactions, especially leadership, negotiation, and both coordinating and motivating others. It also included discipline and resisting coercion, as well as helping others resist fear and panic. They were also daring, making a split-second command decision, or - as earlier mentioned - resisting fear or coercion. They also had to judge the mood and morale of a group of subordinates, or to try and assuage the fears of a group, to rally or inspire others during a difficult situation, or to command the attention or respect of someone hostile. They also had to use reasoning, to consider and evaluate the orders given by a superior, or to find a solution to a difficult diplomatic or legal situation.

Indeed, the operational authority for the starship rested with the Commanding Officer, the Executive Officer, Second Officer, or the Third Officer. These officers had to be able to carefully and precisely coordinate a group of subordinates, or to give detailed orders. The Commanding Officer was responsible for execution of Starfleet orders and policy, as well as for interpretation and compliance with Federation law and diplomatic directives. As such, the Commanding Officer was directly answerable to Starfleet Command for the performance of the ship.

The Main Bridge command chair provided seating and information displays for the Commanding Officer. The command chair was centrally located, designed to maximise interaction with all key bridge personnel, while permitting an unobstructed view of the main viewscreen. The captain's chair featured armrests that incorporate miniaturised status displays, and simplified Conn and Ops controls. Upon keyboard or vocal command, the captain could use these controls to override the basic operation of the spacecraft. Such overrides were generally reserved for emergency situations. The other two seating positions in the command area included somewhat larger information display terminal screens, which permitted these officers to access and input data as part of their duties.

Mission Ops

The aft area of the Theurgy main bridge was Mission Ops, and this was where the Executive Officer oversaw operations ranging from the Master System Display to Tactical CONN coordination. This station was also specifically responsible for monitoring activity relating to secondary missions. In doing so, Mission Ops often had an assistant officer that helped he Executive Officer, relieving him/her of responsibility for lower-priority tasks that must be monitored by a human operator. Although the minute-to-minute assignment of resources would be automatically handled by the Operations station on the bridge, Mission Ops would monitor the computer activity to ensure that such computer control does not unduly compromise any mission priorities. This was particularly important during unforeseen situations that might not fall within the parameters of preprogrammed decision-making software. Essentially, Mission Ops was responsible for resolving low-level conflicts, but would refer primary mission conflicts to the Operations station. Mission Ops generally served as relief for Operations when the duty Ops officer was away from station.

Besides acting as flight control for Tactical CONN, Mission Ops was also responsible for monitoring telemetry from primary mission Away Teams. This included tricorder data and any other mission-specific instrumentation. So, Mission Ops was responsible for monitoring the activities of secondary missions to anticipate requirements and possible conflicts. In cases where such conflicts impact on primary missions in progress, Mission Ops notified the Operations officer. During Alert and crisis situations, Mission Ops also assisted the Tactical Officer, providing information on Tacical CONN, Away Teams and secondary mission operations, with emphasis on possible impact on tactical concerns.

CONN

This was the ship's helm department, which was in charge of handling all flight operations on and off the ship. This meant the Theurgy and all of its support vehicles or any vehicles flying within its vicinity. Instead of the Tactical CONN department flying fighters, the CONN officers operated the shuttles.

The officer at the Flight Control console on the bridge of a starship, often referred to as CONN, was responsible for the actual piloting and navigation of the spacecraft. Although these were heavily automated functions, their criticality demanded a human officer to oversee these operations at all times. The Flight Control Officer (also referred to as CONN or helmsman) received instructions directly from the Commanding Officer. An officer's ability at the CONN covered piloting craft of all sizes, from ground vehicles and shuttles, to grand starships. It also included expertise in all navigation — both on the ground and in space. They had to be able to direct a starship or other vessel through a difficult environment, or to operate a craft with such precision as to aid someone else’s activities. They had to direct a starship or other vessel to avoid a sudden and imminent danger, or to perform extreme or unorthodox maneuvers with a craft using “feel” or “instinct”. They also had to be quick and effective in getting into an EVA suit, including moving through zero-gravity, or resisting the deleterious effects of extreme acceleration or unpredictable motion without an Inertial Dampening Field.

These officers were also experts in judging the nature or intent of another vessel by the way it is moving, or determining the source of a problem with a familiar vessel. They also had to maintain professional decorum and etiquette when representing your ship or Starfleet in formal circumstances, or to argue effectively over a matter of starship protocol, or a course of action.

There were five major areas of responsibility for the Flight Control Officer:

- Navigational references/course plotting

- Supervision of automatic flight operations

- Manual flight operations

- Position verification

- Bridge liaison to the engineering department

During impulse powered spaceflight, the helmsman was responsible for monitoring relativistic effects as well as inertial damping system status. In the event that a requested maneuver exceeded the capacity of the inertial damping system, the computer will request CONN officer to modify the flight plan to bring it within the permitted performance envelope. During Alert status, flight rules permitted the helmsman to specify maneuvers that are potentially dangerous to the crew or the spacecraft. Warp flight operating rules required the CONN officer to monitor subspace field geometry in parallel with the Engineering department. During warp flight, the Flight Control console continually updated long-range sensor data and makes automatic course corrections to adjust for minor variations in the density of the interstellar medium.

Because of the criticality of Flight Control in spacecraft operations, particularly during crisis situations, Conn is connected to a dedicated backup flight operations subprocessor to provide for manual flight control. This equipment package includes emergency navigation sensors.

Specific Duties

- Navigational References/Course Plotting The Flight Control console displayed readings from navigational and tactical sensors, overlaying them on current positional and course projections. Conn has the option of accessing data feeds from secondary navigation and science sensors for verification of primary sensor data. Such cross-checks were automatically performed at each change-of-shift and upon activation of Alert status.

- Manual Flight Operations The actual execution of flight instructions was generally left to computer control, but CONN had the option of exercising manual control over helm and navigational functions. In full manual mode, CONN can actually steer the ship under keypad control.

- Shuttle Operations The Chief CONN Officer would work very closely with the ship's Chief Operations Officer with respect to the use of the ship's shuttle bays, since the Chief CONN Officer was responsible for the pilots flying the shuttles and for training shuttle pilots. Instead of Fighter Bay Ops handling the fighters, the regular Operations personnel - that answered to the Chief Operations Officer - handled the upkeep of the shuttles. Fighter Bay Ops belonged to the Operations department too, they were just specialised at warp fighters, but could be rotated to handle shuttles as well as required.

- Reaction Control System (RCS) Although the actual vector and sequence control of the system was normally automated, CONN had the option of manually commanding the RCS system or individual thrusters.

Bearing & Coordinates

There were five standard input modes available for specification of spacecraft flight paths. Any of these options may be entered either by keyboard or by vocal command. In each case, flight control software would automatically determine an optimal flight path conforming to Starfleet flight and safety protocol. The helm then had the option of executing this flight plan or modifying any parameters to meet specific mission needs.

Normal input modes included:

- Destination planet or stared system Any celestial object within the navigational database was acceptable as a destination, although the system would inform the helmsman in the event that a destination exceeded the operating range of the spacecraft. Specific facilities (such as orbital space stations) within the database were also acceptable destinations.

- Destination sector A sector identification number or sector common name was a valid destination. In the absence of a specific destination within a sector, the flight path would default to the geometric center of the specified sector.

- Spacecraft intercept This requires CONN to specify a target spacecraft on which a tactical sensor locked had been established. This also requires CONN to specify either a relative closing speed or an intercept time so that a speed could be determined. An absolute warp velocity could also be specified. Navigational software would determine an optimal flight path based on specified speed and tactical projection of target vehicle's flight path. Several variations of this mode were available for used during combat situations.

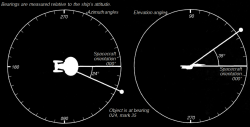

- Relative bearing A flight vector could be specified as an azimuth/elevation relative to the current orientation of the spacecraft. In such cases, 000-mark-0 represents a flight vector straight ahead.

- Absolute heading A flight vector could also be specified as an azimuth/elevation relative to the center of the Milky Way. In such cases, 000-mark-0 represents a flight vector from the ship to the center of the galaxy.

- Galactic coordinates Standard galactic XYZ coordinates were also acceptable as a valid input, although most starfleet personnel generally found this cumbersome.

Tactical

This department was in charge of the ship's weapon systems, their calibrations and upkeep. Furthermore, the tactical officers on starships and starbases were, basically, the ones firing the weapons at the tactical station on the bridge. This role could sometimes be filled by the Chief of Security depending on the officer's experience and responsibilities on the ship.

Tactical officers were men selected from the Academy on account of superior intelligence, reliability and mechanical knowledge. The assignment to Tacical was made with the idea that the officers should be somewhat higher in standard than other officers in regard to starship weaponry and their usage; that their knowledge of ordnance and targeting should be such that they would be able to also make repairs to the systems.

The physical layout of the Tactical station console often described a sweeping curve affording an unobstructed view of the main viewer, and an equally clear view of the command stations on the bridge. This allowed for an uninterrupted exchange between the Tactical Officer and other bridge officers during critical operations, as well as exchanges with crew members occupying the aft stations. The duty station console lacked a seat and was therefore a standup position, deemed ergonomically necessary for efficient tactical functions.

Threat Assessment & Targeting System (TA & TS)

Known colloquially as the “targeting scanners,” the Threat Assessment/Tracking/Targeting System (TA/T/TS) was a ship’s tactical sensors and computer package. The Tactical Officer relied on the TA/T/TS in combat in much the same way as the Flight Control officer uses the navigational computer — it helps him do his job better. Different classes of TA/T/TS were available; the better ones make the Tactical Officer’s job easier, but took up more space and require more power to operate. Ships may have a backup TA/T/TS system to take over for the main system if it was damaged or malfunctioned.

In addition to using it to target weapons and assess tactical data, a Tactical Officer may use targeting scanners to obtain a transporter lock on a person or object, aiding the Ops staff and the Transporter Officers in extracting the target in hostile situations.

Tactical Policies

Starfleet proudly drew upon the traditions of the navies of many worlds, most notably those of Earth. Starfleet honored their distinguished forebears in many ceremonial aspects of their service, yet there was a fundamental difference between Starfleet and those ancient military organizations. Those sailors of old saw themselves as warriors. It was undeniably true that preparedness for battle was an important part of their mission, but Starfleet saw themselves foremost as explorers and diplomats. This might seem a tenuous distinction, yet it had a dramatic influence on the way they dealt with potential conflicts. When the soldiers of old pursued peace, the very nature of their organizations emphasized the option of using force when conflicts became difficult. That option had an inexorable way of becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Peace was no easier than it was in ages past. Conflicts were real, and tensions could escalate at a moment's notice between adversaries who command awesome destructive forces. Yet they had finally learned a bitter lesson from our past: When they regarded force as a primary option, that option would be exercised. Starfleet's charter, framed some two centuries ago after the brutal Romulan Wars, was based on a solemn commitment that force was not to be regarded as an option in interstellar relations unless all other options have been exhausted.

Rules of Engagement

Although starships were fully equipped with sophisticated weaponry and defenses, Starfleet taught its people to use every means at their disposal to anticipate and defuse potential conflict before the need for force arises. This, according to Federation mandate, was Starfleet's primary mode of conflict resolution. Starfleet's rules of engagement were firmly based on these principles. Due to the extended range of Starfleet's theater of operations, it was not uncommon for starships to be beyond realtime communications range of Starfleet Command. This meant a starship captain often had broad discretionary powers in interpreting applicable Federation and Starfleet policies. The details of these rules are classified but the basics were as follows.

A starship was regarded as an instrument of policy for the United Federation of Planets and its member nations. As such, its officers and crew were expected to exhaust every option before resorting to the use of force in conflict resolution. More important, Federation policy required constant vigilance to anticipate potential conflicts and to take steps to avert them long before they escalate into armed combat. Perhaps the most dangerous conflict scenario was that of the unknown, technically sophisticated Threat force. This refers to a confrontation with a spacecraft or weapons system from an unknown culture whose spacefaring and/or weapons capability was estimated to be similar or superior to their own. In such cases, the lack of knowledge about the Threat force was a severe handicap in effective conflict resolution and in tactical planning. Complicating matters further, such conflicts were often First Contact scenarios, meaning cultural and sociologic analysis data were likely to be inadequate, yet further increasing the import of the contact in terms of future relationships with the Federation. For these reasons, Starfleet required cultural and technologic assessment during all First Contact scenarios, even those that occur during combat situations in deep space. Rules of engagement further required that adequate precaution be taken to avoid exposure of the ship and its crew or Federation interests to unnecessary risk, even when a potential Threat force had not specifically demonstrated a hostile intent. There were, however, specific diplomatic conditions under which the starship will be considered expendable.

More common than the unknown adversary was conflict with a known, technically sophisticated Threat force. This referred to confrontation with a spacecraft or weapons system from a culture with which contact has already been made, and whose spacefaring and/or weapons capability was similar or superior their own, even if the specific spacecraft or weapons system was of an unknown type. In such cases, tactical planning had the advantage of at least some cultural and technological background of the Threat force, and the ship's captain would have detailed briefings of Federation policies toward the Threat force. In general, starships were not permitted to fire first against any Threat force, and any response to provocation must be measured and in proportion to such provocation.

Here again, Starfleet required adequate precaution be taken to avoid excessive risk to the ship or other Federation interests. Much more limiting were conflicts with spaceborne Threat forces estimated to be substantially inferior in terms of weapons systems and spaceflight potential. Here again, the use of cultural and technologic assessment was of crucial importance. Prime Directive considerations may severely restrict tactical options to measured responses designed to reduce a Threat force's ability to endanger the starship or third parties. Typically, this meant limited strikes to disable weapons or propulsion systems only. Rules of engagement prohibited the destruction of such spacecraft except in extreme cases where Federation interests, third parties, or the starship itself are in immediate jeopardy.

Even more difficult were conflicts in which a Starfleet vessel or the Federation itself was considered to be a third party. Such scenarios included civil and intrasystem conflicts or terrorist situations. In evaluating such cases, due care had to be taken to avoid interference in purely local affairs. Still, there were occasionally situations where strategic or humanitarian considerations would require intervention. Starfleet personnel were expected to closely observe Prime Directive considerations in such cases.

MVAM Procedure Transcript

For when MVAM is executed via computer and not by use of the auxiliary Battle Bridges.

Captain/Commanding Officer: Engage the multi-vector assault mode.

Computer: Initiating decoupling sequence. Auto-separation in ten seconds. Nine. Eight. Seven. Six. Five. Four. Three. Two. One. Separation sequence in progress.

Tactical Officer: We are in attack formation. Each section is armed and responding to our command.

Captain/Commanding Officer: Attack pattern ["Beta four seven" or the like].

Computer: Specify target.

Captain/Commanding Officer: [State vessel], bearing ["one six two mark seven" or the like].

Computer: Pattern and target confirmed.

[Post battle]

Captain/Commanding Officer: Begin the reintegration sequence then get me a full damage report.

Computer: Reintegration sequence complete.

Attack Patterns

For when MVAM is executed via computer and not by use of the auxiliary Battle Bridges. Each vector can be controlled from the Main Bridge by continuously assigning them attack and defensive patterns. This is done from the Tactical station, with the influx of commands from the commanding officer on the Bridge.

Offensive / Attack Manoeuvres

Alpha

Starfleet's most basic offensive manoeuvre, attack pattern Alpha involves a mostly straight-on approach to the target, with some slight vectoring to the side based on the ship's weapons complement and the target's movement.

Beta-series Manoeuvres

Beta-1

The ship dives down between two enemy ships, firing at least once at each of them (and hoping they themselves will miss and hit each other if properly aligned.

Beta-2

Approaching the target closely, within 90,000 kilometres, the ship jinks to starboard of the target, then dives beneath it to emerge on its port ventral side, firing as it goes.

Beta-3

The ship makes a broad arc turn around one or more ships, attacking them as it goes.

Beta-4

The ship climbs steeply, veering to port or starboard, then quickly dives back down, firing at one or more targets as it goes.

Delta-series Manoeuvres

Delta-1

The ship swoops up from underneath a target to attack its vulnerable ventral side.

Delta-2

The ship swoops over the target from starboard to port, then back from port to starboard (diving underneath the target on the second pass of necessary), firing as it goes.

Delta-3

The ship dives straight down at, or climbs straight up at, the target, firing forward weapons.

Delta-4

An all-out, straightforward frontal attack.

Delta-5

A long, relatively shallow dive to one side of the target (usually whichever way allows the ship to bring the most weapons to bear or which uses the target to take cover from other ships' attacks.

Kappa-series Manoeuvres

Kappa 0-1-0

From a superior position, the ship arcs down and and around its target to port, firing as it goes.

Kappa 0-2-0

The ship flies on a carefully-calculated arc through a battlefield, firing at multiple targets.

Omega-series Manoeuvres

Omega-1

As the ship approaches the target head-on, it jinks to one side and dives steeply from one end of it to another.

Omega-2

The ship rolls from one side to the other giving its weapons maximum exposure so the Tactical Officer can engage multiple targets.

Omega-3

The ship veers back and forth across the battlefield like a darting swallow, attacking vulnerable targets.

Sierra-series Manoeuvres

Sierra-1

The ship swoops in from an aft dorsal angle to attack the target from behind.

Sierra-2

While seeming as if it will pass a particular target, the ship turns to face it head-on and attacks.

Sierra-3

The ship flies through the heart of a battle, jinking back and forth to avoid enemy attacks as it attacks choice targets.

Sierra-4

The ship comes up from beneath the target(s) and loops up over it/them.

Defensive / Evasive Manoeuvres

Alpha-series Manoeuvres

Alpha-1

The ship jinks to one side and dives.

Alpha-2

The ship climbs steeply out of harm's way.

Beta-series Manoeuvres

Beta-1

The ship climbs slightly, then dives down.

Beta 1-4-0

A quick complex manoeuvre involving several rapid turns.

Beta-2

The ship climbs slightly, then jinks hard to port or starboard.

Beta-3

The ship climbs slightly, then jinks slightly to port or starboard and lunges forward.

Beta-4

The ship climbs steeply, then jinks to port or starboard and climbs slightly.

Beta 9-3

A short, rapid dive followed by a quick series of jinks and turns designed to throw off the aim of any opponent.

Delta-series Manoeuvres

Delta-1

As it flies along a relatively straight vector, the ship jinks slightly from one side to the other.

Delta-2

The ship does a barrel roll to go from being in front of its pursuer to above and behind it.

Delta-3

The ship jinks hard to port or starboard and then drops back.

Delta-4

The ship jinks hard to port or starboard and then slides downward in a shallow dive.

Delta-5

The ship jinks hard to port or starboard and then climbs in a shallow, climbs in a shallow, curving arc.

Gamma-series Manoeuvres

Gamma-1

The ship veers to port or starboard in a broad arc, then suddenly jinks in the opposite direction.

Gamma-2

The ship jinks downward in a slight dive to port or starboard, then climbs steeply.

Gamma-3

The ship jinks upward in a slight climb to port or starboard, then dives steeply.

Gamma-4

The ship turns up its side, then falls away in a steep drop to port or starboard.

Gamma-5

The ship dives steeply, turning on its side towards the bottom of the dive and then climbing steeply and levelling out at the end of the climb.

Lambda-series Manoeuvres

Lambda-1

A full starboard roll.

Lambda-2

The ship makes a half-roll and then drops down.

Omega-series Manoeuvres

Omega-1

The ship engages in a complex, stomach-turning series of rapid turns which makes it difficult to track of follow.

Omega-2

The ship jinks to the right, upward, and to the right again.

Omega-3

The ship dives or climbs to port or starboard, executing a long S-turn as it does so.

Omega-4

The ship climbs in an arc, but before reaching the expected top of the arc, it darts quickly forward.

Omega-5

The ship peels off to port or starboard, then executes a turn designed to bring him underneath an enemy ship (perhaps one that was pursuing).

Omega-6

The ship arcs upward to port, then peels down swiftly to the side from the apex of the turn.

Theta-series Manoeuvres

Theta-1

The ship jinks to the side and dives slightly, back to the other side and dives steeply, then climbs about one ship length.

Theta-2

The ship arcs to port around its opponent, then peels downward and to starboard.

Theta-3

The ship peels off to the side, climbing as it does so, then dives straight down.

Theta-4

The ship jinks to starboard, then jinks to port and dives slightly, then jinks back to starboard in a steep dive.

Other Manoeuvres

Cochrane Deceleration

This manoeuvre is efficient when the ship is being pursued by an enemy within 300,000 kilometres. It decelerates suddenly, allowing the enemy to pass it so that it can fire forward weapons.

Picard Manoeuvre

Developed by Captain Jean-Luc Picard in 2355 when he commanded U.S.S. Stargazer, the Picard manoeuvre is only effective against a single target using only lateral sensors, since it relies on a starship's ability to move at faster than light velocities without the target realizing where it's gone. The ship must start out sufficiently far enough from its target that it takes more than five seconds for light to reach the target (more than 1,500,000 kilometres). The ship makes a microwarp burst, thus moving from its current position to one much closer to the target before the target realizes it has moved. The ship drops out of warp, appearing in two places at the same time and fires on the target, hopefully inflicting grievous damage before it realizes what has happened.

Riker Manoeuvre

Developed by Commander William Riker in battle against the Son'a in 2375, the Riker manoeuvre -due to practical considerations- can only be performed in regions of space filled with dangerous, combustible substances such as metreon gas. The ship passes through the gas, collecting it with its Bussard ramscoops. It then flushes the ramscoops, projecting the gas backwards at its pursuers, or forward toward an approaching enemy ship. The enemy's attacks, or a quick phaser blast from the ship ignites the gas, causing an explosion which damages the enemy ship.

Talluvian Manoeuvre

This manoeuvre is a flexible one designed to manoeuvre a ship so that its most powerful phasers are brought to bear on the target for as long as possible. It works best with ships which have streaming phasers rather than pulse phasers. The ship flies above or below its target (depending on which phaserbank is available to use) in a diagonal pattern which allows it to fire its phaser and keeping it locked continuously for as long as possible.

Phonetic Alphabet

The phonetic alphabet is a standardized series of unique sounding words used to spell out letters in order to avoid the confusion of similar sounding letters. Note that some of the letters or numbers have exaggerated pronunciation in order to differentiate them from other words, the numbers five (pronounced "fife" to avoid confusion with the word "fire") and "niner" (to avoid confusion with the German word for "no").

| Alpha (AL fah) | Mike (MIKE) | Yankee (YANG key) |

| Bravo (BRAH VOH) | November (no VEM ber) | Zulu (ZOO loo) |

| Charlie (CHAR lee) | Oscar (OSS cah) | 0 (ZEE ro) |

| Delta (DELL tah) | Papa (pah PAH) | 1 (WUN) |

| Echo (ECK oh) | Quebec (keh BECK) | 2 (TOO) |

| Foxtrot (FOKS trot) | Romeo (ROW me oh) | 3 (TREE) |

| Golf (GOLF) | Sierra (see AIR rah) | 4 (FOW er) |

| Hotel (hoh TELL) | Tango (TANG go) | 5 (FIFE) |

| India (IN dee ah) | Uniform (YOU nee form) | 6 (SIX) |

| Juliet (JEW lee ET) | Victor (VIK tah) | 7 (SEV en) |

| Kilo (KEY loh) | Whiskey (WHIS key) | 8 (AIT) |

| Lima (LEE mah) | X Ray (ECKS RAY) | 9 (NINE r) |

Disclaimer

Starfleet Tactical Emblem used with permission of Gazomg Art - granted Nov 24, 2016 Some edited texts are from the Starfleet Technical Manual.